Biodiversity hotspots in India

Read community contributed articles on biodiversity & environment || Cultural practices & mythological stories related to Indian biodiversity || Official documents related to environment || NGOs, Blogs and Websites || Environment-related video collection || Plants of India || Mammals of India || Facebook || Twitter

Biodiversity hotspots in India

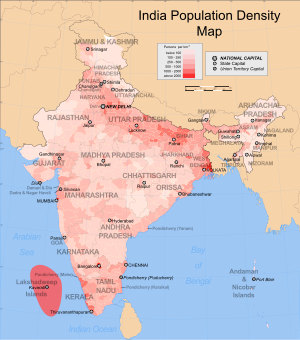

India is one of the richest countries in the world in terms of biodiversity. This natural variation in life is also reflected in the demography of the land. Although the causes behind biodiversity and demographic diversity are different, the human population of the land has depended on the biodiversity in many ways for a long time. At the same time, today, the excessive human population of India is leading to a survival pressure on the biodiversity. Thus, it is important to know and appreciate the diversity in both - human population and flora and fauna.

Demographic diversity of India

Main article: Demographics of India

India is a remarkably diverse country. Arguably, only the continent of Africa exceeds the linguistic, genetic and cultural diversity of the nation of India.[1]. The country houses 1.2 billion people speaking 1652 languages and dialects[2], spread out over more than two thousand ethnicities and over every major religion.

The demographics of India are remarkably diverse. India is the second most populous country in the world, with over 1.18 billion people (estimate for April, 2010), more than a sixth of the world's population. Already containing 17.31% of the world's population, India is projected to be the world's most populous country by 2025, surpassing China, its population exceeding 1.6 billion people by 2050.[3][4] However, India has an astonishing demographic dividend where more than 50% of its population is below the age of 25 and more than 65% hovers below the age of 35. It is expected that, in 2020, the average age of an Indian will be 29 years, compared to 37 for China and 48 for Japan; and, by 2030, India's dependency ratio should be just over 0.4.[5]

This demographic diversity of India is both good and bad for its biodiversity. Bad because of the enormous pressure the human population puts on the natural resources. And good because this human diversity has resulted in a plethora of customs, traditions and rituals in the context of native species. Plants and animals are considered sacred (eg: Ocimum tenuiflorum or Tulsi) or find mentions in mythological stories (eg: Elephas maximus indicus or Indian Elephant) or are used in religious rituals (eg: Nelumbo nucifera or Indian Lotus). These deep associations between biodiversity and culture presents us with a unique opportunity for their conservation. Click this link to read about the cultural associations of Indian biodiversity...

Flora and fauna of India

Main article:Fauna of India and Wildlife of India

India is a country rich in biological diversity. It lies within the Indomalaya ecozone and completely houses two of the 34 biodiversity hotspot in the world[6]. The third - Indo-Burma - lies partially within the Indian North-East.

There is a huge species diversity in India, with several of the species being endemic to the their native ranges in India[citation needed].

| Group |

Number |

% of world species |

| Mammals |

350 |

7.6% |

| Birds |

1224 |

12.6% |

| Amphibians |

197 |

4.4% |

| Reptiles |

408 |

6.2% |

| Fishes |

2546 |

11.7% |

| Flowering plants |

15000 |

6% |

Sources: Indira Gandhi Conservation Monitoring Centre (IGCMC), New Delhi [7] and IISc [8]

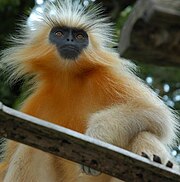

Many Indian species are descendants of taxa originating in Gondwana, to which India originally belonged. Peninsular India's subsequent movement towards, and collision with, the Laurasian landmass set off a mass exchange of species. However, volcanism and climatic change 20 million years ago caused the extinction of many endemic Indian forms.[9] Soon thereafter, mammals entered India from Asia through two passes on either side of the emerging Himalaya.[10] As a result, among Indian species, only 12.6% of mammals and 4.5% of birds are endemic, contrasting with 45.8% of reptiles and 55.8% of amphibians.[11] Notable endemics are the Nilgiri leaf monkey and the brown and carmine Beddome's toad of the Western Ghats. Read more about the origin of India here.....

Biodiversity vs Human progress

Main article: Wildlife of India

According to the 1994 IUCN assessment, India contained 172, or 2.9%, of IUCN-designated threatened species.[12] These include the Asiatic lion, the Bengal tiger, and the Indian white-rumped vulture, which suffered a near-extinction from ingesting the dead bodies of diclofenac-treated cattle.

In recent decades, human encroachment has posed a threat to India's wildlife; in response, the system of national parks and protected areas, first established in 1935, was substantially expanded. In 1972, India enacted the Wildlife Protection Act and Project Tiger to safeguard crucial habitat; further federal protections were promulgated in the 1980s. Along with over 500 wildlife sanctuaries, India now hosts 15 biosphere reserves, four of which are part of the World Network of Biosphere Reserves; 25 wetlands are registered under the Ramsar Convention.

The need for conservation of wildlife in India is often questioned because of the apparently incorrect priority in the face of direct poverty of the people. However Article 48 of the Constitution of India specifies that, "The state shall endeavour to protect and improve the environment and to safeguard the forests and wildlife of the country" and Article 51-A states that "it shall be the duty of every citizen of India to protect and improve the natural environment including forests, lakes, rivers, and wildlife and to have compassion for living creatures."[13]

Biodiversity hotspots

Main article:Fauna of India and Wildlife of India

A biodiversity hotspot is a biogeographic region with a significant reservoir of biodiversity that is under threat from humans. To qualify as a biodiversity hotspot on Myers 2000 edition of the hotspot-map, a region must meet two strict criteria:

- it must contain at least 0.5% or 1,500 species of vascular plants as endemics, and

- it has to have lost at least 70% of its primary vegetation.[14]

Around the world, at least 35 areas qualify under this definition. These sites support nearly 60% of the world's plant, bird, mammal, reptile, and amphibian species, with a very high share of endemic species. Four regions that satisfy these criteria exist in India and are described below. For a more detailed information about these hotspots, go to the Biodiversityhotspots.org homepage

The Western Ghats and Sri Lanka

About the region: The Western Ghats are a chain of hills that run along the western edge of peninsular India. Their proximity to the ocean and through orographic effect, they receive high rainfall. These regions have moist deciduous forest and rain forest. The region shows high species diversity as well as high levels of endemism. Nearly 77% of the amphibians and 62% of the reptile species found here are found nowhere else.[15]. Sri Lanka, which lies to the south of India, is also a country rich in species diversity. It has been connected with India through several past glaciation events by a land bridge almost 140kn wide[16].

How the biodiversity of Western Ghats originated is a still a puzzle. The region shows biogeographical affinities to the Malayan region. More recent phylogeographic studies have attempted to study the origin of Western Ghats using molecular approaches.[17] There are also differences in taxa which are dependent on time of divergence and geological history.[18] Along with Sri Lanka, this region also shows some faunal similarities with the Madagascan region especially in the reptiles and amphibians. Examples include the Sibynophis snakes, the Purple Frog and Sri Lankan lizard genus Nessia which appears similar to the Madagascan genus Acontias.[19] Numerous floral links to the Madagascan region also exist.[20] An alternate hypothesis that these taxa may have originally evolved out-of-India has also been suggested.[21]

Biogeographical quirks exist with some taxa of Malayan origin occurring in Sri Lanka but absent in the Western Ghats. These include insects groups such as the zoraptera and plants such as those of the genus Nepenthes.

Biodiversity: There are over 6000 vascular plants belonging to over 2500 genera in this hotspot, of which over 3000 are endemic. Much of the world's spices such as black pepper and cardamom have their origins in the Western Ghats. The highest concentration of species in the Western Ghats is believed to be the Agasthyamalai Hills in the extreme south. The region also harbors over 450 bird species, about 140 mammalian species, 260 reptiles and 175 amphibians. Over 60% of the reptiles and amphibians are completely endemic to the hotspot. Remarkable as this diversity is, it is severely threatened today. The vegetation in this hotspot originally extended over 190,000 square kms. Today, its been reduced to just 43,000 sq. km. In Sri Lanka, only 1.5% of the original forest cover still remains[16].

The Eastern Himalayas

About the region: The Eastern Himalayas is the region encompassing Bhutan, northeastern India, and southern, central, and eastern Nepal. The region is geologically young and shows high altitudinal variation. Together, the Himalayan mountain system is the world's highest, and home to the world's highest peaks, which include Mount Everest and K2. To comprehend the enormous scale of this mountain range, consider that Aconcagua, in the Andes, at 6962 metres is the highest peak outside Asia, whereas the Himalayan system includes over 100 mountains exceeding 7200 metres[22]. Some of the world's major river systems arise in the Himalayas, and their combined drainage basin is home to some 3 billion people (almost half of Earth's population) in 18 countries. The Himalayas have profoundly shaped the cultures of South Asia; many Himalayan peaks are sacred in Hinduism, Buddhism and Sikhism.

Geologically, the origin of the Himalayas is the impact of the Indian tectonic plate traveling northward at 15cm per year to impact the Eurasian continent, about 40-50 million years ago. The formation of the Himalayan arc resulted since the lighter rock of the seabeds of that time were easily uplifted into mountains. An often-cited fact used to illustrate this process is that the summit of Mount Everest is made of marine limestone.[23]

Biodiversity: The Eastern Himalayan hotspot has nearly 163 globally threatened species including the One-horned Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis), the Wild Asian Water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis (Arnee)) and in all 45 mammals, 50 birds, 17 reptiles, 12 amphibians, 3 invertebrate and 36 plant species[24][25] The Relict Dragonfly (Epiophlebia laidlawi) is an endangered species found here with the only other species in the genus being found in Japan. The region is also home to the Himalayan Newt (Tylototriton verrucosus), the only salamander species found within Indian limits.[26]

There are an estimated 10,000 species of plants in the Himalayas, of which one-third are endemic and found nowhere else in the world. Five families - Tetracentraceae, Hamamelidaceae, Circaesteraceae, Butomaceae and Stachyuraceae - are completely endemic to this region. Many plant species are found even in the highest reaches of the Himalayan mountains. For example, a plant species Ermania himalayensis was found at an altitude of 6300 metres in northwestern Himalayas![27]. A few threatened endemic bird species such as the Himalayan Quail, Cheer pheasant, Western tragopan are found here, alongwith some of Asia's largest and most endangered birds such as the Himalayan vulture and White-bellied heron[27].

The Himalayas are home to over 300 species of mammals, a dozen of which are endemic. Mammals like the Golden langur, The Himalayan tahr, the pygmy hog, Langurs, Asiatic wild dogs, sloth bears, Gaurs, Muntjac, Sambar, Snow leopard, Black bear, Blue sheep, Takin, the Gangetic dolphin, wild water buffalo, swamp deer call the Himalayan ranged their home. The only endemic genus in the hotspot is the Namadapha flying squirrel which is critically endangered and is described only from a single specimen from Namdapha National Park[27].

Indo-Burma

About the region: The Indo-Burma region encompasses several countries. It is spread out from Eastern Bangladesh to Malaysia and includes North-Eastern India south of Brahmaputra river, Myanmar, the southern part of China's Yunnan province, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Cambodia, Vietnam and Thailand. The Indo-Burma region is spread over 2 million sq. km of tropical Asia. Since this hotspot is spread over such a large area and across several major landforms, there is a wide diversity of climate and habitat patterns in this region.

Biodiversity: Much of this region is still a wilderness, but has been deteriorating rapidly in the past few decades. In recent times, six species of large mammals have been discovered here: Large-antlered muntjac, Annamite muntjac, Grey-shanked douc, Annamite striped rabbit, Leaf deer, and the Saola. This region is home to several primate species such as monkeys , langurs and gibbons with populations numbering only in the hundreds. Many of the species, especially some freshwater turtle species, are endemic. Almost 1,300 bird species exist in this region including the threatened white-eared night-heron, the grey-crowned crocias, and the orange-necked partridge. It is estimated that there are about 13,500 plant species in this hotspot, with over half of them endemic. Ginger, for example, is native to this region. [28]

Sundaland

| Sundaland is a region in South-East Asia that covers the western part of the Indo-Malayan archipelago. It includes Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei and Indonesia. India is represented by the Nicobar Islands. The United Nations declared the islands a World Biosphere Reserve in 2013. The islands have a rich terrestrial and marine ecosystem that includes mangroves, coral reefs and sea grass beds. The marine biodiversity includes several species such as whales, dolphis, dugong, turtles, crocodiles, fishes, prawns, lobsters, corals and sea shells [29]. The primary threat to this biodiversity comes from over exploitation of marine resources. In addition, the forests on the island also need to be protected. |

Reasons for biodiversity loss in hotspots

There are four main reasons why species are being threatened in these biodiversity hotspots

- Habitat destruction: As recently as 30 years ago, most of the regions in these biodiversity hotspots were inaccessible and remote. Now, due to better infrastructure, contact of these areas with humans has increased. Activities such as logging of wood, increased agriculture, increased human habitation has led to destruction of forests and pollution of rivers. These factors are causing species ranges to reduce and habitats to become choppy. The government planned to establish habitat corridors, but these plans have not yet materialized in most areas. Activities such as mining, construction of large dams, highway construction has also caused significant destruction of habitats[30].

- Resource mismanagement: Increased tourism without proper regulation has led to pollution and environmental degradation. Prime example are pilgrimage destinations like Rishikesh and hill stations like Dehradoon. These spots, once nestled in the pristine ranges of the Himalayas, are now dirty commercial destinations. Places like Dehradoon are even experiencing a construction boom so large that illegal immigrants from Bangladesh are also flocking there[31]. Religious destinations in the Himalayas, where devotees flock in millions now, are also hot destinations for medicinal plant trade, which has threatened plant life in the area.

- Poaching: Large mammals such as the tiger, rhinoceros and the elephant once faced the distinct possibility of complete extinction due to rampant hunting and poaching. However, efforts by conservationists since the 1970s has helped stabilize and grow these populations. Still, the trade in tiger hide, elephant tusks, tiger teeth, rhinoceros horn remains profitable and rampant[32][33].

- Climate change: Although dire IPCC predictions of Himalayan glaciers melting by 2035 have been retracted[34], there is no doubt that several Himalayan glaciers are melting[35][36]. In the Western Ghats, studies have shown that the deciduous and the evergreen forests of Karnataka are the most at risk[37][38]. Climate change may significantly affect the temperatures, rainfalls and water tables in the Western Ghats, according to an assessment by the Government of India.

Recent extinctions

The exploitation of land and forest resources by humans along with hunting and trapping for food and sport has led to the extinction of many species in India in recent times. These species include mammals such as the Indian / Asiatic Cheetah, Javan Rhinoceros and Sumatran Rhinoceros.[39] While some of these large mammal species are confirmed extinct, there have been many smaller animal and plant species whose status is harder to determine. Many species have not been seen since their description.

Hubbardia heptaneuron, a species of grass that grew in the spray zone of the Jog Falls prior to the construction of the Linganamakki reservoir, was thought to be extinct but a few were rediscovered near Kolhapur in Maharashtra.[40]

Some species of birds have gone extinct in recent times, including the Pink-headed Duck (Rhodonessa caryophyllacea) and the Himalayan Quail (Ophrysia superciliosa). A species of warbler, Acrocephalus orinus, known earlier from a single specimen collected by Allan Octavian Hume from near Rampur in Himachal Pradesh was rediscovered after 139 years in Thailand.[41][42]

Further reading and external sites

- Official flora and fauna of India A list of official flora and fauna of various states in India

- Biodiversity profile of India

- Biodiversity significance of North East India for the study on Natural Resources, Water and Environment Nexus for Development and Growth in North Eastern India. A paper by Forests Conservation Programme, WWF-India.

Semantic tags

Browse all Semantic Tags associated with this page

- Browse all Semantic Tags associated with this page

- Find more pages and articles created by the community by clicking this link.

| Title | Biodiversity hotspots in India | Article is on this general topic | General interest | Author | Gaurav Moghe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific location(s) where study was conducted | Not noted | General region where study was conducted | Not noted | State where study was conducted | Pan-India |

| Institutional affiliation | Not noted | Institution located at | Not noted | Institution based around | Not noted |

| Species Group | Not noted | User ID | User:Gauravm | Page creation date | 2011/10/05 |

Share this page:

Comments

blog comments powered by DisqusReferences

- Major sections of this article have been copied from the following articles on Wikipedia: Demographics of India, Fauna of India and Wildlife of India article Accessed November 2010

- ^ India, a Country Study United States Library of Congress, Note on Ethnic groups

- ^ Mother Tongues of India According to the 1961 Census

- ^ BBC - India's population 'to be biggest' in the planet

- ^ United States Census Bureau - International Data Base (IDB)

- ^ India's demographic dividend

- ^ Hotspots by region

- ^ Indira Gandhi Conservation Monitoring Centre (IGCMC), New Delhi and the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP), World Conservation Monitoring Center, Cambridge, UK. 2001.

- ^ Biodiversity profile for India.

- ^ K. Praveen Karanth. (2006). Out-of-India Gondwanan origin of some tropical Asian biota

- ^ Tritsch, M.E. 2001. Wildlife of India Harper Collins, London. 192 pages. ISBN 0-00-711062-6

- ^ Indira Gandhi Conservation Monitoring Centre (IGCMC), New Delhi and the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP), World Conservation Monitoring Center, Cambridge, UK. 2001. Biodiversity profile for India.

- ^ Groombridge, B. (ed). 1993. The 1994 IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK. lvi + 286 pp.

- ^ Krausman, PR & AJT Johnsingh (1990) Conservation and wildlife education in India. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 18:342-347

- ^ Myers, N. et al. Nature 403, 853–858 (2000)

- ^ Daniels, R. J. R. (2001) Endemic fishes of the Western Ghats and the Satpura hypothesis. Current Science 81(3):240-244

- ^ a b Biodiversityhotspots.org (Western Ghats and Sri Lanka) at the Hotspots explorer. Accessed: Oct 11, 2011

- ^ Karanth, P. K. (2003) Evolution of disjunct distributions among wet-zone species of the Indian subcontinent: Testing various hypotheses using a phylogenetic approach Current Science, 85(9): 1276-1283

- ^ Biswas, S. and Pawar S. S. (2006) Phylogenetic tests of distribution patterns in South Asia: towards an integrative approach; J. Biosci. 31 95–113

- ^ Affinities of Sri Lankan reptiles

- ^ Biogeography of Madagascar

- ^ Karanth, P. 2006 Out-of-India Gondwanan origin of some tropical Asian biota. Current Science 90(6):789-792

- ^ Yang, Qinye (2004). Himalayan Mountain System. ISBN 9787508506654. http://books.google.com/?id=4q_XoMACOxkC&pg=PA25&lpg=PA23&dq=%22South+Tibet+Valley%22. Retrieved 2007-08-07.

- ^ A site which uses this dramatic fact first used in illustration of "deep time" in John McPhee's book Basin and Range

- ^ Conservation International 2006

- ^ Ecosystem Profile: Eastern Himalayas Region, 2005

- ^ Amphibian Species of the World - Desmognathus imitator Dunn, 1927

- ^ a b c Biodiversity hotspot.org (Himalayas) at the Hotspots Explorer. Accessed: Oct 10, 2011

- ^ Biodiversity hotspots.org (Burma) Accessed: Nov 15, 2010

- ^ Report:COMMITTEE CONSTITUTED TO HOLISTICALLY ADDRESS THE ISSUE OF POACHING IN THE ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS Sep 2011

- ^ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedHotspots - ^ At India-Bangladesh Border, Living in Both, and Neither NYTimes. Published: Oct 10, 2011. Accessed: Oct 10, 2011

- ^ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedHostpots - ^ Pardoned Poacher Arrested with Rhino Toes in Nepal Rhinoconservation.org. Accessed: Oct 10, 2011

- ^ IPCC retracts 2035 alarm on Himalayan glacier melt Times of India. Published: Jan 21, 2010. Accessed: Oct 16, 2011.

- ^ Rivers of ice: Stunning images of the Himalayas show how much glaciers have shrunk over 80 years Dailymail.co.uk. Published: Oct 14, 2011. Accessed: Oct 16, 2011

- ^ Glacier lakes: Growing danger zones in the Himalayas Published: Oct 16, 2011. Accessed: Oct 16, 2011

- ^ Northern and central parts of Western Ghats most vulnerable to climate change Published: Aug 17, 2011. Accessed: Oct 16, 2011

- ^ Climate change and forests in the Western Ghats A presentation by Dr. R. Sukumar, CES, IISc

- ^ Vivek Menon (2003). A field guide to Indian mammals. Dorling Kindersley, Delhi.

- ^ IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) E-Bulletin - December 2002 [1] Accessed October 2006

- ^ Threatened birds of Asia [2] Accessed October 2006

- ^ The Nation, March 6, 2007